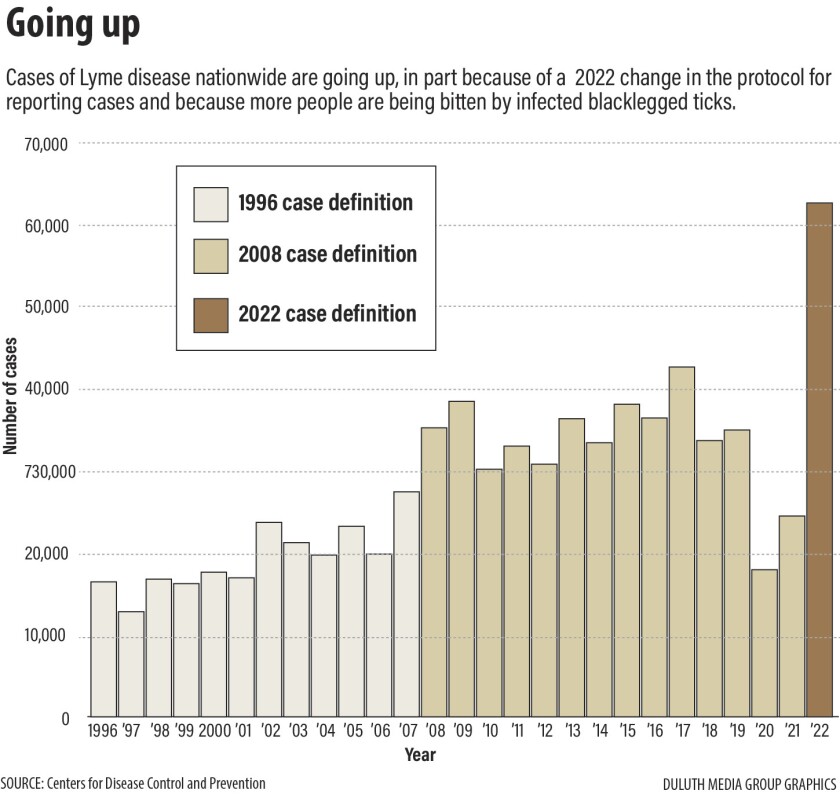

DULUTH — Lyme disease cases reported to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention skyrocketed in 2022, the most recent year data is available, but mostly because of a change in how the disease is reported and not because of many more tick bites.

That’s the latest report from the Minnesota Department of Health as the Northland heads into the peak time for tick exposure — spring and early summer — and the peak time for exposure to the many serious diseases ticks carry.

“We usually see our peak for cases reported in July and August,” said Elizabeth Schiffman, epidemiologist supervisor of the Vectorborne Diseases Unit of the Minnesota Department of Health, “and because there’s a lag time from exposure (tick bite), that means it really starts when Minnesotans get outside in big numbers when the weather gets nicer in May and June.”

But tick season has been starting earlier and lasting longer in recent years. While cases usually drop off to nothing each winter, that didn’t happen in the warm, no-snow winter of 2023-24.

“Our tick season never ended from last year into this year,” Schiffman told the News Tribune. “We had new reports of ticks in December and January, and we really haven't seen that before in Minnesota.”

ADVERTISEMENT

In 2022, about 63,000 cases of Lyme disease were reported across the U.S. to state health agencies and to the CDC. That’s more than double the 24,661 cases in 2021, mostly because national standards for reporting Lyme cases, starting in 2022, now allow for more cases to be counted. But even with the changes, the CDC admits that their official number is still far lower than the actual number of people being treated for Lyme and similar diseases, now estimated at nearly a half-million people nationwide each year.

New York continues to have the most officially reported cases of Lyme at 16,758 in 2022, followed by Pennsylvania and New Jersey. But Wisconsin, with 5,208 cases, now has the fourth-most Lyme disease cases in the nation. Minnesota is also in the top 10 nationally, with 2,685 cases in 2022. Both western Wisconsin and eastern Minnesota are national hotspots for Lyme.

Whether the Midwest’s warm, mostly snowless winter will mean more ticks and more tick disease through 2024 isn’t yet clear. Spring weather can have a big impact, both on tick survival and on how many people go outdoors.

“They have always been able to adapt to our snowy winters, and because they do overwinter, we won't really know if this year's (hatch) will be bigger for some time yet,” Schiffman said. “But one thing we have seen is that we are getting to peak tick activity earlier in the year than we used to see.”

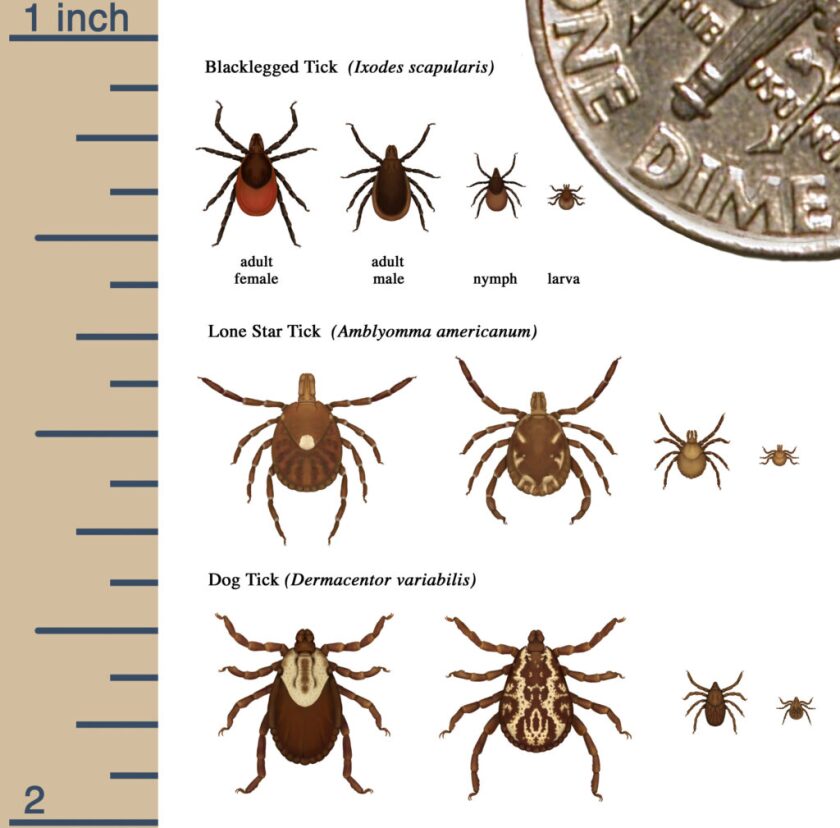

Not only is Lyme continuing to increase, but the notorious alpha-gal allergic reaction, spread only by the lone star tick, is increasing in Minnesota. That tick was rarely reported in the past but is showing up more often in Minnesota, spreading the still rare but potentially life-threatening disease that can make people severely allergic to eating meat.

Both the disease and the tick that carries it are expanding enough, Schiffman said, that health officials are considering making alpha-gal an officially reportable disease, requiring health care providers to report cases to get a better handle on its spread.

Researchers are finding more and more disease-causing viruses in the ticks they look at, well beyond just the Lyme virus. So they are going back to check what else ticks might carry that medical science hasn't documented yet.

“There’s no doubt” there are viruses in ticks now that are making people sick but which haven't yet been identified, said Benjamin Clarke, a University of Minnesota Duluth biologist who heads the medical school’s research on tick-borne diseases. Those uncategorized diseases may be similar to but not quite the same as Lyme.

ADVERTISEMENT

“It’s really still a hidden epidemic, and climate change is making it worse,” he said. “We don’t even know how many more pathogens might be in this one type of tick. That’s what I'm looking at now.”

Time to protect yourself

As the number of cases increases, many people who spend time outdoors still aren’t taking the situation seriously enough to protect themselves.

Ticks are out as soon as the snow melts. Each morning, they crawl out of the damp leaves and duff on the ground, up onto a blade of grass, flower or a weed, stick their arms out, and wait for a warm-bodied host to walk past.

In the Northland, spring turkey hunters (who often sit on the ground), ATV riders, mushroom hunters, shore anglers, campers, gardeners and anyone going for walks are vulnerable, as are people who work outside like wildlife technicians, wildland firefighters and utility crew members.

If warm weather persists, even fall deer hunters are susceptible to tick bites. Experts say ticks are more numerous in open and partially open areas, such as fields and yards, and less numerous in very deep woods.

Not only are more people being diagnosed with tick-borne diseases as Northlanders and their doctors become more aware of the risks and symptoms, but more ticks in more places across the region are carrying the disease. A much higher percentage of deer ticks now carry the bacteria that causes Lyme disease than a decade ago.

“About half the blacklegged ticks we look at now are carrying the (bacteria that causes Lyme), so it’s a 50-50 chance if you have a (blacklegged) tick bite,” Clarke said. “But if you count all the pathogens we know about, we found at least one of those in 87% of the ticks we looked at.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Many doctors specializing in tick diseases say that any bite from a black-legged tick should now be treated, usually with antibiotics, as if it’s assumed the tick carries disease, and the sooner the better.

To remind Northlanders of the potential problems, the News Tribune is again publishing a compilation of the latest information we’ve found on what ticks and tick-borne diseases are out there and what you can do to keep yourself from getting very sick.

Blacklegged ticks and Lyme disease: What to watch for

Lyme disease is an infection caused by the bacteria Borrelia burgdorferi. This spiral-shaped bacterium is spread by the bite of a blacklegged tick, formerly called a deer tick. The disease is named after Lyme, Connecticut, where it was first identified in the U.S. in 1975.

Blacklegged ticks require a blood meal at each stage of their life — larval, nymph and adult — and can spread disease after they have that first blood meal on an infected rodent. For a month or so after a known tick bite, watch for symptoms including a red spot, often shaped like a bull's-eye, or rash near the bite site, full body rash, neck stiffness, headache, nausea, weakness, muscle or joint pain or aches, fever, chills and swollen lymph nodes.

Eventually, as the disease progresses without treatment, some victims report muscle weakness on one or both sides of the face; immune-system activity in heart tissue that causes irregular heartbeats; pain that starts from the back and hips and spreads to the legs; pain, numbness or weakness in the hands or feet; painful swelling in tissues of the eye or eyelid, even vision loss.

In the later stage of Lyme, untreated, some victims have reported mood changes, cognitive issues and even sleep disorders and heart problems. In some cases, severe arthritis symptoms occur, as can Bell's palsy nerve issues.

ADVERTISEMENT

Other tick-borne diseases

- Anaplasmosis: Spread by blacklegged ticks. This bacterial disease causes fever, severe headache, muscle aches, chills, shaking, nausea, vomiting, weight loss, abdominal pain, diarrhea and mental fatigue. Usually most severe in the aging or immune-compromised. Severe complications can include respiratory failure, renal failure and secondary infections.

- Babesiosis: Spread by blacklegged ticks. This rare and life-threatening infection of the red blood cells is caused by tiny parasites called babesia. Previously found only on the East Coast and California; confirmed in Minnesota and Wisconsin. Signs start one to eight weeks after a tick bite. Symptoms include body aches, chills, fatigue, fever, headache, loss of appetite and sweating. You also can get a condition called hemolytic anemia in which your red blood cells die faster than your body can make new ones.

- Powassan encephalitis: Spread by blacklegged ticks, squirrel ticks and groundhog ticks. Symptoms include fever, headache, vomiting and weakness. Can cause severe disease, including infection of the brain; encephalitis; infection of the membranes around the brain and spinal cord; and meningitis, which can cause confusion, loss of coordination, difficulty speaking and seizures. About 1 in 10 people with severe disease die, and half who survive severe disease have long-term health problems such as recurring headaches, loss of muscle mass and strength and memory problems.

- Ehrlichiosis: Spread by blacklegged ticks and lone star ticks. Caused by the bacteria Ehrlichia chaffeensis, E. ewingii and E. muris eauclairensis. Symptoms include fever, chills, headache, muscle aches and sometimes upset stomach.

- Alpha-gal syndrome (also called alpha-gal allergy, red meat allergy and tick bite meat allergy): Spread by the lone star tick. It is a serious, potentially life-threatening allergic reaction, not an infection. Symptoms occur after eating red meat and include hives or rash; nausea or vomiting; heartburn or indigestion; diarrhea; cough; shortness of breath or difficulty breathing; drop in blood pressure; swelling of the lips, throat, tongue or eyelids; dizziness or faintness; and severe stomach pain.

- Rocky Mountain spotted fever (also called dog ticks): Spread by wood ticks. This bacterial disease causes fever, headache and rash. Can be deadly if not treated early with the right antibiotic. The number of cases has risen in the last two decades from 495 cases in 2000 to a peak of 6,248 in 2017. It has been confirmed in Minnesota and Wisconsin and is more common in the Dakotas.

Tick prevention: DEET and permethrin

Experts strongly suggest using both a personal insect repellent on your skin and a repellent that can be applied to clothing.

- DEET: By far the most effective insect repellent, including for keeping ticks away. Multiple studies have found that in concentrations of 30% and under, it's considered safe to use on human skin. Other options include picaridin, a synthetic compound first made in the 1980s to resemble the natural compound piperine, found in the plants that produce black pepper.

- Permethrin: Keep this off the skin, but spray on clothing or soak clothing in diluted permethrin to keep ticks and other insects at bay for long periods, often several washes. Permethrin, which kills the insect, is considered extremely effective and also works to keep away mosquitoes that may be carrying viruses like West Nile, zika and malaria.

- Clothing: Ticks usually crawl onto people below the knees and then crawl upward. Wear long-sleeved shirts and long pants. Wear light-colored clothes so it is easier to see ticks. Tuck pants inside socks to keep them on the outside of your clothing, giving you more time to see and remove them before they get to your skin and start feeding. Several companies, including insectshield.com and LL Bean, sell clothing pretreated with permethrin that is said to last much longer. You can also send your clothes to the Insect Shield to be treated.

- Tick check: Experts suggest checking yourself in front of a mirror after coming in from outdoors, or better yet, have someone else help check you. Hotspots are around the waist, under the arms, inner legs, behind the knees and around the head, including in and around the ears and in hair. Adults should help check their young children for ticks.

- Take a shower. The force of the water running over you will help wash off any unattached ticks you can’t see. (Simply submerging the ticks in water for a short time, while bathing or swimming, doesn’t necessarily kill them.)

- Remove ticks: Prompt removal of embedded ticks helps reduce the chance a disease will be transmitted. Ticks need to be attached for six to 24 hours to transmit disease to humans. The best method for removing a feeding tick is to grasp it as close as possible to the skin of the host with tweezers or tissue paper. Do not squeeze the tick if possible. Gently, yet firmly, apply steady pressure on the tick until you pull it out. If you try to jerk or twist the tick out, you risk the mouthparts breaking off and remaining in the skin. Clean out the wound with a good germicidal agent, such as iodine, to help prevent infection. Experts say using tape, alcohol or Vaseline to cover the tick and cause it to voluntarily pull its mouthparts out of the skin is ineffective.

- Save ticks: If there is any question as to whether this tick is a species that can potentially transmit disease, especially blacklegged, save it by placing it in a small container to be identified later.

If you get sick after a tick bite

- Call your doctor if you experience symptoms or are bitten by multiple ticks in a short time even without symptoms. The good news is that even the most serious cases can be treated, and patients get better, with antibiotics.

- The antibiotic Doxycycline can be a lifesaver. Several doctors suggest having a single 1,000-milligram dose of doxycycline on hand in case you are bitten by a blacklegged tick, especially if you spend a lot of time in tick-infested areas and expect to be away from medical care. The single dose is often effective at preventing tick-borne disease like Lyme from taking hold.

- Dogs are also susceptible to several tick-borne illnesses, including ehrlichiosis, Lyme disease, anaplasmosis and others. Most veterinarians suggest using a medication such as Frontline, K9-Advantix or Vectra 3D or a tick collar. Many vets also suggest getting dogs vaccinated against Lyme disease.

Who gets sick from ticks in Minnesota?

- 62% of tick-borne illness victims are men.

- Average age is 45.

- 68% experienced symptoms in June or July, which corresponds with the most active period for blacklegged ticks (May-August).

- 67% developed the bull's-eye rash.

- 36% developed serious issues such as arthritis or Bell’s palsy.

- Cases are reported where patients live. But more than half the cases either lived in or recently spent time outdoors in the most tick-prone areas of eastern Minnesota or western counties in Wisconsin.

Did you know?

- A blacklegged tick in its resting mode may take only one breath per day while waiting for a blood meal.

- Ticks sense your presence by the carbon dioxide you exhale and your body heat and wake up quickly to attack.

- A female blacklegged tick may lay up to 4,000 eggs in the fall, but only about 5% will live long enough to take a blood meal the next spring.

- Ticks are born sterile and pick up diseases from small critters such as field mice. Higher rodent populations often mean more ticks and more tick-borne disease. The diseases don't impact the rodents.

- Blacklegged ticks need a blood meal during each of their nymph, juvenile and adult stages of life.

Blame mice, and birds, not deer

While the bacteria that causes Lyme is present in small mammals like mice everywhere, there is something unusually conductive in the saliva in the blacklegged tick that can transmit it to people. It's the only tick that can do it, and scientists aren’t sure why.

Blacklegged ticks were once commonly called deer ticks. But a better nickname would have been mouse ticks. According to several studies, the number of white-footed field mice around indicates how much tick-borne illness is around.

"People living in northern and central parts of the U.S. are more likely to contract Lyme disease and other tick-borne ailments when white-footed mice are abundant," a study in the journal Ecology noted. "Mice are effective at transferring disease-causing pathogens to feeding ticks."

ADVERTISEMENT

Fluctuations in mouse populations due to predators, food, weather or other factors may be one reason Lyme disease cases fluctuate yearly even as they trend up over the long term. In some areas, researchers are working to see if increasing predators that eat mice can effectively reduce mouse populations and thus reduce the rate of Lyme disease. Ticks also don't like very cold winters, although a blanket of snow can keep them snug and alive.

Experts also now think birds are moving the most ticks the farthest distance, allowing ticks and the diseases they carry to spread much faster than they would by riding on land mammals.

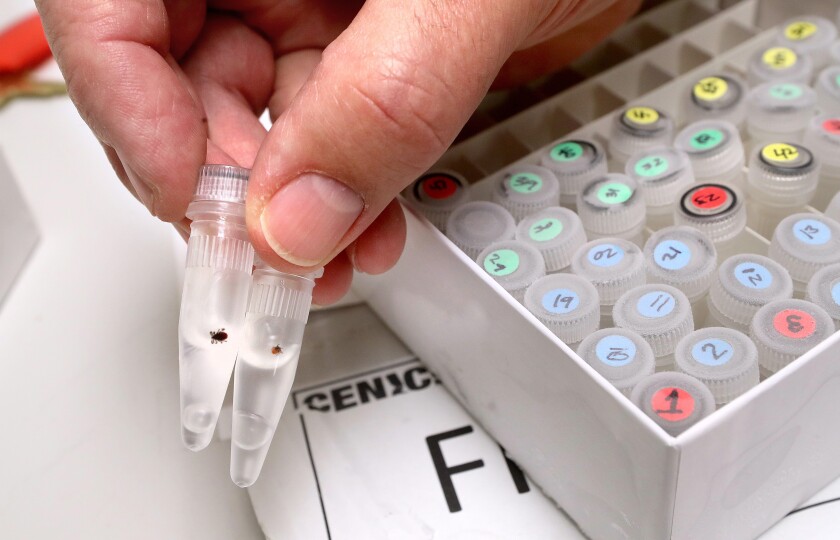

Send your ticks to UMD’s Ixodes Outreach project

If you find a tick, University of Minnesota Duluth biologist Benjamin Clarke wants it. Clarke coordinates a program of undergraduate students collecting and analyzing blacklegged ticks (Ixodes scapularis) to determine which ones carry the Lyme bacteria and map where they are found.

You can also request a free tick kit with a tick ID card, a tick removal key and specimen submission materials. Clarke also brings his tick and Lyme show on the road for community outreach group presentations.

Clarke is starting to look closer at wood or dog ticks to see what diseases they are carrying, including Rocky Mountain spotted fever.

Send your request to ixodesoutreach@gmail.com or place the tick in a zip-top bag and mail it to Ixodes Outreach Project, 1035 University Drive, Duluth, MN 55812.

When submitting a tick, indicate where the tick was found; the date it was found; whether it was attached to a person or animal; and if you would like to receive additional information, provide your name, mailing address and/or email.

ADVERTISEMENT

The project's goal is to promote awareness of health concerns associated with Lyme disease and tick-borne diseases in Northeastern Minnesota’s isolated Arrowhead region. The Ixodes Outreach Project is a part of the University of Minnesota Medical School, Duluth Campus Department of Biomedical Sciences.