Darkness is falling outside the window of William Eggleston’s fifth-floor apartment in midtown Memphis, and the silences that punctuate his conversation have grown even longer. After several hours in his company, I am preparing to take to take my leave, when suddenly he decides he is going to play the piano for me. I help him to his feet and he makes his way unsteadily to the magnificent Bösendorfer grand in the corner of his living room. Once seated, he stares for a few long moments at the keyboard, as if lost in thought.

“I play the piano maybe two or three times a day,” he told me earlier, “but only if she wants to be played. I speak to her and she talks back. Mostly, just to say: ‘What’s in there?’ She is almost always responsive.”

This evening, the piano wants to be played. The 78-year-old photographer, who has imbibed several glasses of bourbon-on-ice in the past hour or so, calls up a snatch of a Beethoven piano sonata from memory. It is the starting point for a long extemporisation that unfolds slowly and tentatively at first, becoming more complex and compelling as his concentration becomes total. Time seems to slow down in the room as the reflection of his wristwatch dances on the wall behind him and the light fades on the treetops beyond the window. The mystery that is William Eggleston deepens.

In his eighth decade, the man whom many consider the world’s greatest living photographer has surprised the art world by releasing his debut album on the indie rock label Secretly Canadian. Entitled Musik, it comprises 13 often dramatic improvisations on compositions by Bach (his hero) and Handel as well as his singular takes on a Gilbert and Sullivan tune and the jazz standard On the Street Where You Live. Even more surprising, to those of us who have witnessed his serene piano playing on several occasions over the years, the works are played entirely on a Korg synthesiser (bought in the 1980s and now broken beyond repair), and assume the character of experimental electronic soundscapes.

The original recordings survive on 49 floppy discs that amount to around 60 hours of improvisation. Producer Tom Lunt, a friend of his son, Winston, undertook the mammoth task of editing and remastering the tapes. Eggleston professes to have had “nothing whatsoever” to do with the selection of tracks or the release of the album. The results are by turns challenging and mesmerising. “There’s the same sense of freedom you find in his photography,” Lunt said recently of the album, while Eggleston’s close friend the film director David Lynch has described it as “music of wild joy with freedom and bright, vivid colours”. The great washes of synthetic sound, sometimes seductively symphonic, sometimes ominous, certainly add a new resonance to the photographer’s most famous quotation about being “at war with the obvious”.

Last year I interviewed Eggleston on stage at the National Portrait Gallery in London; he was in a wheelchair following a bad fall. Today, he moves through the apartment with the aid of a silver-topped cane, which accentuates his aristocratic demeanour. He is as stylish as ever in a white dress shirt with a red, paisley-patterned Ascot, untied, falling from the collar, pressed formal trousers and shiny Oxford brogues. For years, he had his suits made to order on Savile Row, but now, he tells me, they are provided by Stella McCartney, whom he refers to, with a twinkle in his eye, as his current favourite “girlfriend”. Another of his “girlfriends”, Alex, an artist who hails from Hot Springs, Arkansas, and whose work is pinned to the wall behind him, arrives towards the end of our meeting to keep him company. “There are quite a few of them out there,” he says, smiling mischievously.

Following the death of his wife, Rosa, in 2015, Eggleston reluctantly vacated the family home for this large apartment in a well-heeled residential “retirement community”. Alongside the piano stands a state-of-the-art hi-fi system and some huge speakers. “One of the advantages of being here is that all the neighbours are deaf. I can play the piano loudly all night if I want to. I often do.”

He remains defiantly intemperate, getting through a pack of Natural American Spirit cigarettes during our conversation and visibly livening up as his “cocktail hour” arrives. It begins at 5pm and ends around 8pm, unless he has polished off his daily alcohol allowance (half a bottle of Jack Daniel’s Black Label) before then, which is often the case. Things can get quite surreal by the second glass. The next day, he will tell me that he has more than half a million negatives, which seems a lot. When I mention it to his son, Winston, he informs me that there are in fact around 55,000.

Given that Eggleston began playing the piano, he says, aged four, I ask him if he regrets not becoming a concert pianist (as his parents briefly hoped he might). “I can say no because I don’t have much of a desire to perform in public,” he responds. “When I play, I’m really playing for myself. If friends are around when that happens, they often say: ‘Oh, Bill, it’s so beautiful. I’d love to hear that again.’ And I say: ‘Well, I didn’t write it down.’ It’s here and it’s gone – like a dream.”

When I inquire whether he is classically trained, he looks at me askance. “I can read scores but I cannot sight read. Not that it matters. Sight reading is nothing to do with the aesthetics of music. In fact, people who are good at it absolutely cannot improvise.” For him, playing the piano alone each day is a kind of meditation. If others are present, though, it is a different story. “I need a drink down me to give me courage to play you something,” he says early on. “It really does help. A little bit of alcohol, as you must know, calms one down and lets one think not so much about the world out there but what’s in here.” (He taps his forehead.)

Music, rather than photography, now takes up more of his time. “I dream often, almost every day, about beautiful pieces of music,” he says, wistfully. “I wake up and rush over to the piano and I can’t remember any of them. Like dreams, when they’re gone, they’re gone.”

In art or life, William Eggleston has never adhered to tradition. Derided by critics in the early 70s as a vulgarian for daring to shoot the everyday in vivid colour, he is now regarded as a master of the medium. Other photographers had used colour, including Saul Leiter, Fred Herzog, Helen Levitt and his friends William Christenberry and Stephen Shore, but no one had done so with the same vivid tonal palette and disorienting compositional force. “What he was doing in the 70s,” Martin Parr once remarked, “was so far ahead of the game that it was revolutionary.”

In terms of influence, only Robert Frank’s book The Americans (1958) casts a longer shadow than William Eggleston’s Guide (1976), its title both a statement of intent and a mischievously subversive poke at the idea that great photography can be taught. A catalogue for his controversial MoMA show, it comprised just 48 images of often quotidian subjects – a blazing barbecue, milk cartons scattered on waste ground, the interior of an oven – as well as wilfully casual portraits of local people. “For my generation, he is more influential even than Frank,” says Alec Soth, perhaps the finest of the current generation of American documentary photographers. (Soth’s image of Eggleston hunched over a keyboard adorns the cover of Musik.) “I doubt there is anyone shooting in colour today who has not been influenced by his early work. For me, The Guide is the guide.”

Eggleston’s photographs have travelled way beyond the photography and art world, influencing the style of film-makers such as Sofia Coppola and Gus Van Sant, and appearing on album sleeves by Big Star in 1974, and more recently on Primal Scream’s Give Out But Don’t Give Up (1994) and the 2006 EP Joanna Newsom & the Ys Street Band. “They are just gifts from me to people I like,” he says.

“Eggleston sees the beauty in the things and places that other people find commonplace or even ugly,” says Primal Scream’s Bobby Gillespie. “He transforms them somehow and the heightened sense of reality in his best pictures is so intense it is almost hallucinatory in its electric glow.”

It was not always thus. On hearing that Eggleston had abandoned black-and-white in the early 70s, his friend the French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson told him: “You know, William, colour is bullshit.” When John Szarkowski, the visionary curator of the Museum of Modern Art, showed Eggleston’s work in 1976, the reviews were savage: his work was dubbed banal, boring and even described as “cracker chic”. The New York Times called it “the most hated show of the year”. The negative criticism upset Szarkowski, but not Eggleston, who had shown up late for his own opening, having fallen asleep in his hotel room following one too many afternoon drinks. “The controversy did not bother me one bit,” he says, “Those few critics who wrote about it were shocked that the photographs were in colour, which seems insane now and did so then. What’s more, they didn’t explain why it so shocked them. To me, it just seemed absurd.”

His detractors, though, were offended, not just by how he photographed but by what he chose to photograph. On his travels around the American south and beyond, Eggleston pointed his camera at the sky above him and the earth below, at rooftops, road signs, puddles, deserted roads, the packed interior of a freezer, the light falling on a ketchup bottle on a diner tabletop. When people appear in his photographs, they often look beatific in the soft southern sunlight or dazed by their excesses. His friend and fellow southerner the novelist Eudora Welty said of his work: “In landscapes, cityscapes, street scenes, roadside scenes, at every sort of public converging-point, in dreaming long view and arresting close-up, through hours of dark and light, he sets forth what makes up our ordinary world. What is there, however strange, can be accepted without question; familiarity will be what overwhelms us.”

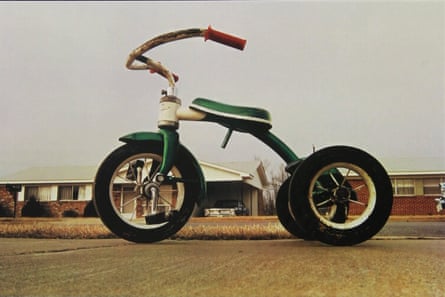

Eggleston later described his approach as “photographing democratically”, but he was also, unconsciously or otherwise, photographing conceptually. His gaze imbued every subject with equal meaning, whether a child’s bicycle, a row of dolls on a car hood or a naked man standing dazed in a dishevelled room. “By the time he published The Democratic Forest (his second book, in 1989), there is really no adherence to the principle of the decisive moment, which had so dominated photography for decades,” says Soth. “It is a conceptual conceit of pure openness, more akin to the composer John Cage’s idea that you should be attuned to the presence of everything around you at all times. Only someone so instinctively gifted and confident as Eggleston could have pulled it off. Many others have since tried and failed to do the same.”

Eggleston’s radical eye for composition, all those skewed angles and odd perspectives, was, he once told me, informed more by Cezanne’s paintings than by any photographic precedents. Coupled with his instinctive understanding of the unsettling power of colour, his democratic approach challenged the conventions of photography as radically as Warhol had challenged ideas of painting and print-making in the previous decade. In the early 70s, Eggleston accidentally discovered the dye-transfer printing process that American advertisers were using to imbue their magazine images with an almost unreal atmosphere. He began using it too, sensing correctly that it would transmit the singular intensity of his vision of an everyday America that was both strangely beautiful and trashy.

One of his best known images, Greenwood Mississippi (1973), more commonly referred to as “The Red Ceiling”, depicts from below a bare lightbulb and three white electric cables leading to it against a shiny crimson-painted ceiling. Like several Eggleston images, it is mundane in terms of subject matter and broodingly ominous in its atmosphere. “It’s like red blood that’s wet on the wall,” he once said. “It shocks you every time.” Was it, though, a record of what he actually saw or an intensification, even an exaggeration, of it? “It was the most accurately reproduced version of what I saw, if that makes sense.” So, the red ceiling really was that red? He nods. “The prints I have seen of it were not artificially enriched at all. That’s why I use the word ‘accurately’.”

Eggleston’s America was, and to a degree remains, both familiar in its vernacular iconography and alien in its almost Martian otherness. The novelist Donna Tartt detected “a sparkle of menace” in his most powerful images, a reading he remains baffled by. “I have been told that people have felt that in the pictures, but I don’t see it myself.”

What was once perceived as vulgar is now acknowledged as visionary. Following his somewhat belated embrace by the fine art world (last year, after five years with the Gagosian gallery, he shifted to David Zwirner), those once-derided dye transfer prints have rocketed in value. In 2012 at Christie’s, New York, 36 of Eggleston’s vintage prints from the 1970s sold for close to $6m. One of the most famous – a child’s tricycle shot from street level to appear loomingly larger than life – fetched a startling $578,500.

Eggleston seems blithely unconcerned by this, as only people from old money can be, while also being utterly assured – in his elegant, unassuming way – of his own genius. Alongside making music, he has been drawing and painting – abstract colour works that fill hundreds of notebooks – even longer than he has been making photography. “I haven’t tried writing yet, but I still might,” he says, smiling. “Drawing, painting and photography we could say are all run by the same rules – which don’t really exist.”

To make sense of the contradictions that define William Eggleston, the gentility and the wildness, the elegance and the excess, one must consider his childhood on a cotton plantation in the Mississippi Delta. Born in Memphis in 1939, he grew up in the small town of Sumner, two hours’ drive away, where his grandfather, Joseph A May, was the judge. When Eggleston’s father, who studied engineering, married the judge’s daughter, he was given one of the family’s cotton plantations to run, which he did reluctantly and with little success. His parents, Eggleston tells me, were “much more progressive and understanding than the rest of the family so I did not have what you might call a traditional strict southern upbringing. In fact, not at all.”

When she was asked to describe his childhood, Eggleston’s late mother, whom he once photographed clandestinely with a surveillance camera, described him as “very brilliant, very strange, separate from his confreres”. To a degree, that remains the case. As a child, he played the piano a lot, created collages and drawings, and was fascinated with all things electrical. “I recall being really excited just by the idea of electricity. Still am, in fact,” he says. “Like music, it is something one can’t see, but is there.” He tells me he carried out a lot of different experiments and “blew a lot of fuses around the house”.

Aware that he was different, his family left him pretty much to his own devices until he was dispatched, aged 15, to the very exclusive Webb school in Bell Buckle, Tennessee. He later described it as “callous and dumb”. Did his family expect him to continue the family cotton business? “No, as I recall, they did not seem to mind a bit that I had no inclination to become involved in agriculture. There’s a saying down here about ‘watching the cotton grow’. That’s fine as far as it goes but it gets a little bit boring after a while. One could say that one has to be suited to it temperamentally,” he says, drawing out each syllable of the word. “I was not.”

He first met his future wife, Rosa Kate Byrne Dosset, who was from even grander southern stock, when she was four years old and came to stay with his family after the suicide of her mother. “Terrible thing,” he says. “And she really did not get on with her real father or indeed her grandmother, who sent her off to fancy girls’ schools all over the place. So Rosa would come out to one of our country places so often she was practically, unquestionably a member of the family. It was as if she didn’t really have a family until she got to know mine.”

He tells me they “courted” for 10 years before getting married and confirms that they once were the talk of Memphis for driving around in matching powder-blue Cadillacs. “We had some good times,” he whispers, and falls into a private reverie. He must miss her deeply, I say. He nods. “You know, it’s more a sustained feeling of shock. She died so instantly and unexpectedly. She was not sick. I doubt there is anything worse, but it is not yet a matter of grief for me, which makes me feel sort of guilty. I had assumed the shock would be a quick and passing thing, but for me that’s not the way it is.”

He and Rosa grew up in what was still the old, segregated south. Did it mark him in any way? “Not much. The negroes that I grew up around were really like family members. They grew up around us and their families were born in the main houses. That’s just the way it was.” I sense that he had little contact with, or interest in, the social upheavals of the late 1960s in America: the Vietnam war protests, the hippy movement, civil rights. “No, not one bit. Whenever it was that civil rights happened, though, we lost all our labour. They all moved to Chicago or somewhere like that.” On the door of his apartment, beneath his name is a postage stamp depicting the pioneering Civil Rights activist, Rosa Parks. I take it he was pro-civil rights? “I didn’t see anything wrong with it,” he says, matter-of-factly. “I never did think about it much, to tell you the truth.”

And yet his photographs often address, obliquely yet powerfully, the discontents of the American south he was born into. A portrait of a besuited white man and his white-jacketed black chauffeur, both standing and listening attentively to a funeral service that is happening beyond the frame, evokes the south’s entire history of racially determined deference, protocol and power. A picture of a confederate flag, reflected in a puddle, with the title Troubled Waters, now seems even more prescient in its suggestion of a fading political past and uneasy present.

Part of the complex dynamic that underpins Eggleston’s work, and perhaps even more so his life, is the tension between his temperament, which tends towards the excessively libertarian, and his social position as a white southerner born into wealth and privilege at a time when the old south was on the wane. Other than taking photographs, which he does not depend on for a living, he has not had to work a day in his life. Even so, his creative self-absorption seems extreme even by artistic standards. “It could be that I was always little bit selfish in what it was I wanted to do,” he says, “so I was not ever that interested in what Joe Blow was interested in.” Does he believe that one needs to be selfish to be an artist? “Now, that’s an interesting question. Put it this way, I don’t see anything wrong with that. I think you are right that maybe a really fine artist possibly has to be selfish. Maybe that is just part of the puzzle of being an artist.”

Age has mellowed William Eggleston, allowing one to savour his soft southern charm without negotiating the craziness of old. “He really is elegant in every way, culturally as well as sartorially, so it is always a privilege to spend time in his company,” says his friend the French fashion designer Agnès B, an avid collector of photography. “As well as being one of the greatest artists alive today, he is truly individual: polite, kind and – how shall I say it? – naughty, but in a very elegant way.”

Naughty is one way of putting it. Back in the 1970s, Eggleston’s reputation for dissolution was such that one local acquaintance of his, the late musician and producer Jim Dickinson, compared him to Keith Richards, which, one suspects, appalled Eggleston, who has no love for rock’n’roll. Though tales of his appetite for excess are legion, he refuses to talk about his younger, wilder self, considering it the epitome of poor taste. Suffice to say his fondness for alcohol, women, guns and prescription drugs – he had the same private pharmacist as Elvis, the notorious “Dr Nick” Nichopoluous – often landed him in trouble.

A Vanity Fair profile from 1991, which featured a portrait of him dressed in English tweeds and riding boots, holding a rifle, traced the outlines of Eggleston’s cavalier life: his two houses, one shared with his wife, Rosa, the other with his long-term girlfriend, Lucia Burch; several outstanding arrest warrants for drunk-driving and a few overnight stays in the local jail for shooting firearms indoors. “Lucia and I have shot at each other several times,” he told the writer Richard B Woodward “She once aimed a .410 shotgun at me. Those pictures of mine on the walls aren’t there just because she likes them. They’re covering up bullet holes, some of them.”

When Alec Soth called in at Eggleston’s house unannounced during an initial road trip for his book, Sleeping By the Mississippi, in 1999, he found him lying unconscious on the ground outside. Soth recalls the scene: “You have to realise, I’m 30 years old, this is my hero and there he is sleeping on the ground outside his door. I was just flabbergasted. I gently woke him up and he said: ‘She’s locked me outta the house again, goddammit.’ Then he got up and asked me to drive him to the store for some smokes.”

Soth ended up having lunch with Eggleston, who had no idea or interest in who he was or why he had dropped by, and then Soth drove him to another store which sold rare stamps. “He was was an avid stamp collector so I waited while he bought a bunch of expensive stamps, which he ended up leaving in my car.”

Eventually they went back to the house, where Eggleston agreed to pose for a portrait, but abruptly changed his mind after Soth had set up a chair outside on the porch. The afternoon ended abruptly, when Rosa appeared, saw her favourite chair on the porch and ordered Soth to leave. “In fact, she locked me out. So the photograph on the Musik album cover was actually taken though the back door just before Eggleston passed out again.”

In a profile on CBS news recently, Eggleston’s daughter, Andra, a textile designer who has recently created a series of dresses with Agnès B based on his drawings, spoke of the confusion his philandering caused her as a child. She recalled how an ex-mistress of his had once thrown a brick through the window of the family home and how her mother had threatened to do the same back in retaliation. “I spent my entire life just wanting to be normal,” she said, adding: “Everything my dad did at that time ended up in the papers.”

So his marriage to Rosa, I venture now, did not follow conventional lines. “I guess not,” he says, reaching for the pack of cigarettes, and looking off into the distance to signal that this was not a subject to pursue. One of his lovers – the erstwhile Warhol “superstar” Viva, with whom he lived for a time in the Chelsea hotel in New York in the mid 70s – once described him as “an exaggeration of the worst in every man”. Have they kept in touch? “Oh yes, we are still close. She lives in California now and I see her when I go out there. She’s a wonderful lady.” I ask after Marcia Hare, whose younger self, pale and angelic, appears in one of my favourite photographs by him, lying spread out on the grass holding a camera in her outstretched hand. (She was, it turns out, zonked on quaaludes, the sedative of choice for the Memphis demimonde of the time.) “Oh, Marcia is still very much around. I see her from time to time but not so much now. Maybe two or three times a year. We’re not boyfriend and girlfriend, but we get along just perfectly. Same with Viva and all the others. I don’t know why,” he laughs. “I must be lucky, I guess.”

When I ask if he has any regrets, he says: “I don’t think I regret things. Maybe there’s some things I should [smiling], but I’m not aware of them. There may be ghosts in the closets I don’t know about.”

His life, I suggest, has been one long series of improvisations. Likewise, his way of going out into the world to take photographs. He thinks about this for a long moment, then nods. “I’ve never thought that exactly, but now you mention it, it must be so. Why not?” So, there is an affinity between the taking of a photograph and the making of a piece of music? “I think so, yes. There must be some connection but it remains utterly mysterious to me.”

He drags on his cigarette and closes his eyes in deep thought. A silence worthy of Samuel Beckett ensues, before he opens them again and, exhaling slowly, continues: “What I will say is that it’s practically impossible for me to explain in words anything at all about an image. So I don’t ever try to express the power of my photographs. I think I can say exactly the same thing about a piece of music. It is what it is and words just don’t seem to fit.”

Musik is out now on Secretly Canadian

Cover stories: Eggleston’s album images

Big Star: Radio City (1974)

William Eggleston’s most famous image, Greenwood, Mississippi, (1973), also known as The Red Ceiling, appeared on the cover of Big Star’s second album. Eggleston knew lead singer Alex Chilton and played piano on Nature Boy, a track on the group’s third album, 3rd. “We were friends, but it had absolutely nothing to do with his music. In fact, I couldn’t stand his music.”

Alex Chilton: Like Flies on Sherbert (1979)

Chilton used another of Eggleston’s images for his solo album. The image of dolls on a car bonnet against a bright blue sky perfectly suited the album’s disconnected songs.

Primal Scream: Give Out But Don’t Give Up (1994)

When Primal Scream were recording at Ardent studios in Memphis in 1993, they paid a visit to Eggleston who gave them permission to use his image of a neon Confederate flag reflected in a puddle. “I like their music. I think the photograph is in the right place,” he said recently. The group also used Eggleston’s images on the covers of their singles Dixie-Narco, Dolls and Country Girl. The latter – which portrayed Eggleston’s muse/lover, Marcia Hare, outstretched on the grass holding a camera – was also used as the cover of Chuck Prophet’s 2004 solo album, Age of Miracles, and on Ali Smith’s novel The Accidental.

Green on Red: Here Come the Snakes (1989)

Green on Red used an ominous Eggleston image of an axe resting atop a barbecue entitled Afterward from the Democratic Forest (1988). Lead singer Chuck Prophet said later: “We did a lot of hanging out, listening to Doris Day records at earsplitting volume... Eggleston would bring up wine from his cellar and play the harpsichord. Photos were spread haphazardly on the tabletop. He’d push ’em around and eventually he pulled one out and said: ‘This is the one.’”

Spoon: Transference (2010)

The band’s seventh studio album features Eggleston’s image of his nephew stretched out and looking bored. “I love that photo,” Spoon’s frontman Britt Daniel told Vanity Fair. “You can make up storylines just from the look on that kid’s face. It was the perfect photo for that record, gave the album a little bit of mystery and depth.”

William Eggleston: Musik (2017)

Musik, Eggleston’s debut album of electronic music, was released last month. It features a portrait of the photographer at home, hunched over a keyboard. It was taken by Alec Soth through the back door of Eggleston’s house after the younger photographer, who had paid an impromptu call on his hero, had been ejected by Eggleston’s late wife, Rosa. SO’H

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion