Snatching the prize for the first gaffe of the campaign, the Tory propaganda unit posted video footage of Boris Johnson in the back of a car explaining why we need an election while apparently not wearing a seatbelt.

That’s appropriate because the Tory leader is taking a spin on a foggy and potholed electoral highway not fitted with the usual safety features and in winter, when surfaces can be very slippery.

Even the most bullish Tories privately acknowledge that this election is a huge roll of the dice. The range of plausible results is wide and the Brexit-scrambling of traditional party allegiances has rendered the old blue-red swingometer a near-useless instrument of prediction. The potential outcomes include Mr Johnson returning to Number 10 with the chunky majority and personal mandate that he craves, and another hung parliament in which every other party has said they will not co-operate with the Conservatives even if they are again the largest cohort.

The campaign begins with most of the opinion polls awarding the Tories a hefty lead. This is not as much of a comfort as it would once have been. When one newspaper klaxoned “Boris soars into 17-point poll lead”, it was not Labour candidates who were made most jumpy – it was Tory ones. They are inevitably haunted by memories of 2017, when a monster poll lead at the outset of Theresa May’s campaign ended with the Tories losing their majority. It is also worth remarking that the Conservatives are not a popular government and Mr Johnson is not a well-rated prime minister. The vote share indicated by polling is down on what Mrs May achieved in her humiliating victory of two years ago.

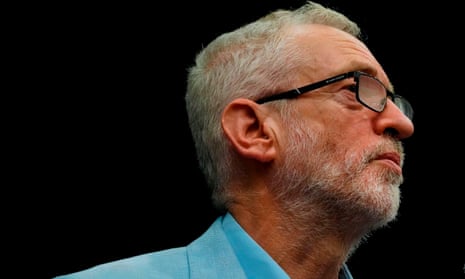

The Tory leader owes his lead to the dismal ratings for Labour. Few Labour MPs think Jeremy Corbyn can win this contest and history suggests that they are correct. It is not so much the headline number that says this, but underlying metrics. No opposition leader has ever removed the incumbent and become prime minister when the challenger is less well regarded as a candidate for the premiership and his party is rated inferior on economic competence. You can fail on one of these tests and still become prime minister. Margaret Thatcher did that in 1979. She was less rated as a candidate for Number 10 than Jim Callaghan, but the Tories led on economic competence. Tony Blair did it in 1997. Labour was rated lower on economic competence, but he was rated higher for leadership than John Major. What no one has ever done is fail both tests and become prime minister.

Mr Corbyn launched his campaign with the humblebrag that the election was “not about me”. But a lot of it will be, whether he likes it or not. All modern campaigns have a presidential dimension and this has become truer as the years have passed. Voters rightly take a view about the character of the person whom a party is asking them to make prime minister. Precedents exist to be broken and all that, but for Mr Corbyn to get to Number 10 he has to fight a campaign that sensationally improves both his personal ratings and his party ratings by polling day or he has to defy a law that has always previously been iron.

We cannot be sure what the real meaning of this election will be until we have got to the end of it, but we already know what the parties would like to be the story. Each has a competing narrative that they will be trying to make the most compelling between now and 12 December. The Tory leader’s story is that he needs a parliamentary majority to “get Brexit done”. It won’t. Even if this election produces a Commons that will pass the withdrawal agreement, there will then be years of negotiating the future relationship with the EU, accompanied by economic turbulence. I said “get Brexit done” was his story, not that it was necessarily true.

The Lib Dems, presenting themselves as “the strongest party of Remain”, will have a matching interest in making this an election defined by the one issue. The Opinium poll that we publish today suggests that the proportion of people saying that they will base their vote on Brexit has more than doubled since 2017 from 18% to 40%. That still leaves a substantial segment of the electorate whose choice will not be determined by Brexit alone. There’s some hope in that for Labour, a party that will prefer to talk about anything but its tortured position on Brexit and its leader’s continuing refusal to say whether he is for or against it. Labour’s story will be that Britain needs a radical break from nine years of “failed Tory austerity”, a pitch similar to the one that helped Mr Corbyn surge from a low base to an inspirational defeat two years ago.

If a clear winner emerges from this election, it will be because one party has succeeded in making its preferred narrative resonate more powerfully than those of its rivals. Yet it is highly possible that, in a nation divided not just on Brexit but its other priorities, no single story can prevail.

No election script, however carefully gridded into the campaign schedule and however relentlessly pre-tested on focus groups of swing voters, survives first contact with the unexpected. A very early example of that was when “Donald from Washington” phoned in to Nigel Farage’s radio show. I suppose you could argue that it ought to have been entirely predictable that the US president would come galumphing into the British election campaign, but no Conservative I know expected it to happen this early or this unhelpfully. His lavish, if confused, endorsement of Mr Johnson delighted Labour campaigners. In every election of my adult life, Labour has accused the Tories of planning to sell off the health service, but it seems to be getting some extra bite to that attack by suggesting that the Johnson Brexit would see the NHS flogged off to US pharma companies. If it could be arranged, Labour would love to have Mr Trump make an intervention in our election on a daily basis.

There will be many strange features of this first December election since 1923. In several respects, it is already like no other campaign I have known. One is that the Conservatives have willed this contest while knowing that it is extremely likely that they are going to lose MPs, notably in Scotland, the south-west and Remain-leaning areas of London and the home counties. Tory hopes of prevailing are pinned on taking seats from Labour, some of which have never had a Conservative MP. These are Brexity constituencies in the Midlands, the north of England and Wales. A Tory think-tank has already given us the first voter stereotype of the campaign. This is “Workington Man”, a white, older, socially conservative, rugby league fan who can help the Tories to victory if he can be persuaded to abandon his traditional allegiance to Labour.

As Nick Timothy, Mrs May’s chief of staff during the 2017 election, has acknowledged, this is essentially the strategy he formulated and then failed to execute. It is true that Mr Johnson enjoys being at the centre of a campaign a lot more than his wooden and introverted predecessor and he is much better than her at retail politics. It would be hard, after all, to be worse. Tories hope that they will avoid the egregious blunders of her effort. But Mr Johnson will have to be a very skilled seducer to overcome the multigenerational cultural aversion to the Tories in the areas that he is targeting.

His chances are complicated, and most probably reduced, if Nigel Farage goes ahead with his threat to field a Brexit party candidate in every constituency. There’s a lively argument about whom this would hurt most, but the evidence suggests that it is more likely to be the Conservatives. The polling indicates that for every 2017 Labour voter that the Brexit party has taken, it has taken two voters off the Conservatives. It will be a rather delicious irony if the Tory assumption that a split in the Remain vote will gift them a majority is wrecked by a mirroring division among the Leave vote.

Some battles are won before a single shot has been fired. Some elections are foregone conclusions, the result written in the stars long before the campaign begins. This contest, conducted before an unprecedentedly volatile electorate, which has little faith in any of the competitors, will be fought to the last shot. A lot can happen in the next six weeks and much of it will be beyond the control of the principal players. Fasten your seatbelts now.